Rome

Plamen Dejanoff

November 28, 2019 – July 25, 2020

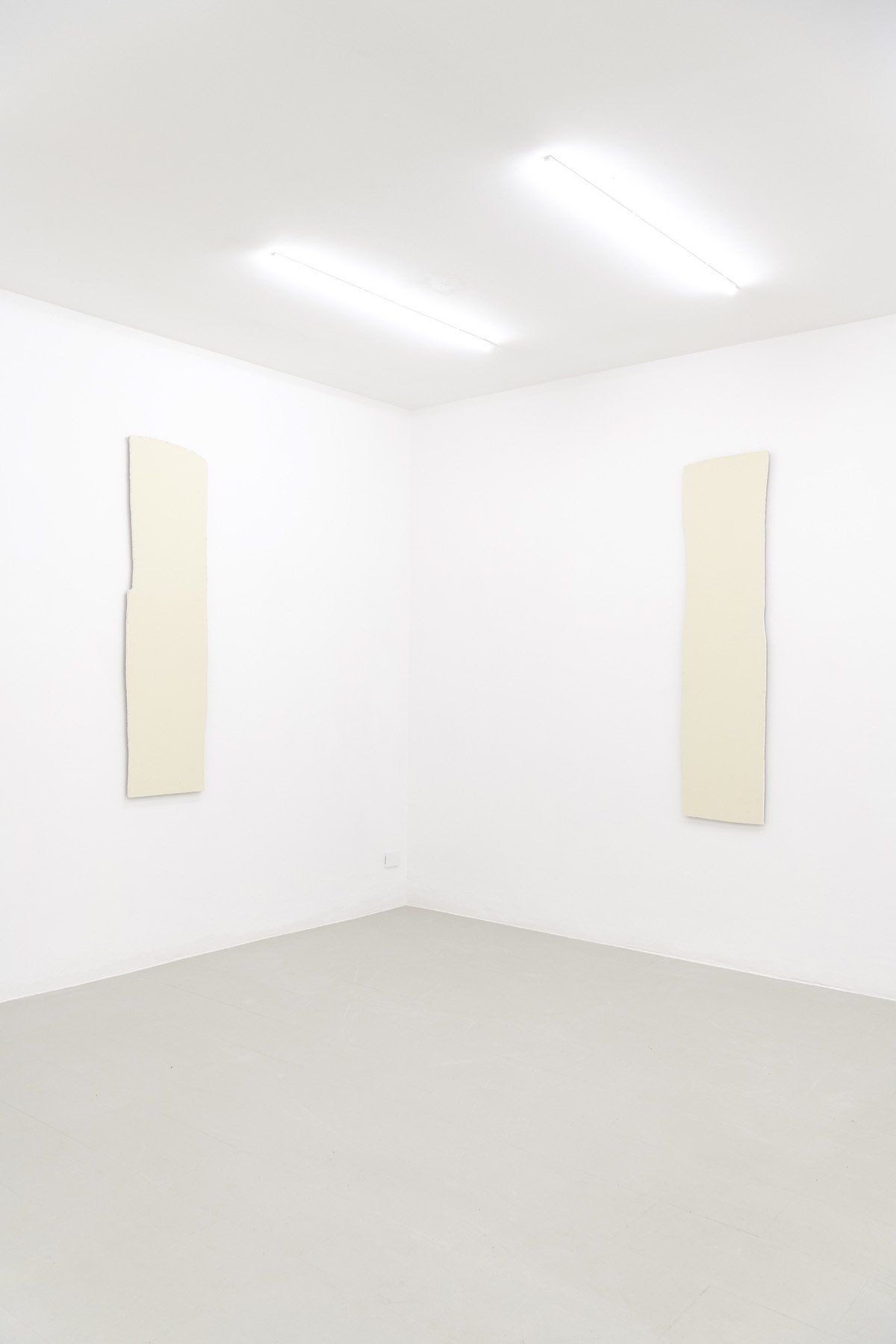

Plamen Dejanoff, 2019

Installation view

Layr, Rome

Plamen Dejanoff, 2019

Installation view

Layr, Rome

Plamen Dejanoff

Untitled, 2019

Aluminium sculpture, plexi, six porcelain sculptures

229 × 126 cm

Detail view

Plamen Dejanoff

Untitled, 2019

Aluminium sculpture, plexi, six porcelain sculptures

229 × 126 cm

Plamen Dejanoff, 2019

Installation view

Layr, Rome

Plamen Dejanoff, 2019

Installation view

Layr, Rome

Plamen Dejanoff

Untitled, 2019

Aluminium sculpture, plexi, six porcelain sculptures

Detail view

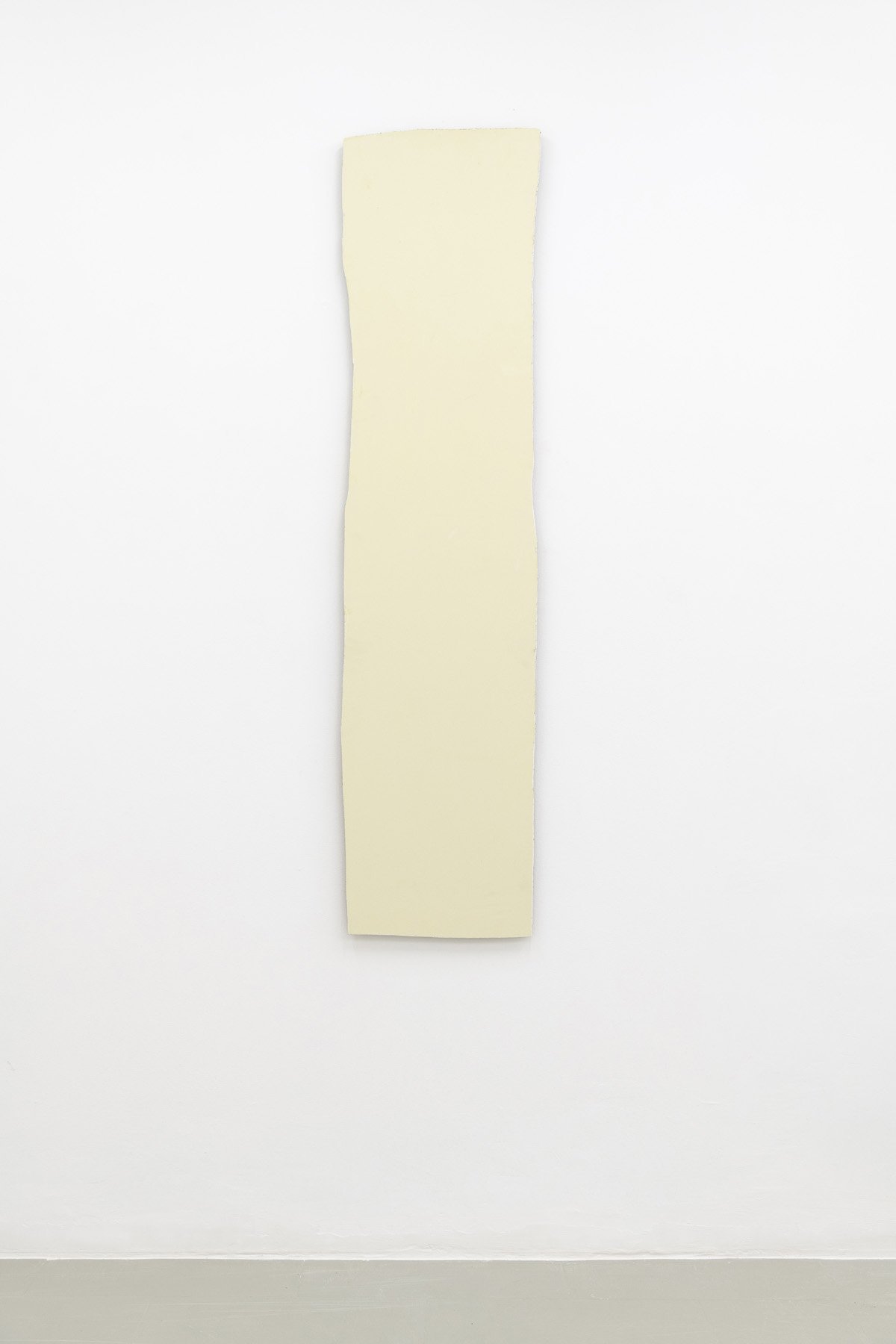

Plamen Dejanoff

Untitled (Palais Slav), 2019

Plasterboard wall

190 × 51 cm

Plamen Dejanoff

Untitled (Palais Slav), 2019

Plasterboard wall

151 × 46 cm

Plamen Dejanoff, 2019

Installation view

Layr, Rome

Plamen Dejanoff

Untitled (Palais Slav), 2019

Plasterboard wall

190 × 45 cm

Plamen Dejanoff

Untitled (Palais Slav), 2019

Plasterboard wall

184 × 47 cm

Photos: Giorgio Benni

Veliko Tarnovo is a small town in the centre of Bulgaria with a turbulent history. It was the scene of numerous battles between the Slavs and Ottomans and the site where the nation’s first democratic constitution was drawn up in 1879. Le Corbusier came to Veliko Tarnovo in 1911 to study the architecture of the town, lined up along the foothills of the Balkan Mountains with the houses connected to one another like a modular system.

The Slav Palace stands in the town centre. Built around 1720, it remains the tallest building in town (excepting the churches, of course). The forty closely staggered window arches on the top floor are clearly visible from afar. During the communist era the palace was owned by the state and interior walls were erected to divide the spacious rooms into smaller residential units. For many years plasterboard fixtures concealed the stucco, historic structure and in some cases, entire rooms.

Plamen Dejanoff’s family, following a restitution procedure, consolidated the Slav Palace and others of the city’s historic buildings into the “Foundation Requirement” trust, and during the renovation work, Dejanoff uncovered some of these old features. By removing historical layers, he unmasks the political past of his homeland while at the same time quoting art historical examples such as Gordon Matta-Clark and Laurence Weiner. While in their work, the emptiness on the walls or in the space brought about through reconstruction, attacks urban or institutional narratives, Dejanoff takes the stories of the uncovered structures even further.

The German plasterboard panels installed in the historic Bulgarian palace in recent years to continue the fulfillment of a socialist-communist ideal of a fair distribution of living space have been painted in various colours. Dejanoff has cut out pieces of these panels, in sizes varying from human-scale to dimensions reminiscent of traditional portrait paintings. He also removed the metal structure of the supporting profiles in order to reassemble them in Rome. It is thereby less about reconstructing the Bulgarian room than about highlighting another level of alienation and reinterpretation of the building material. What do the dismantled components of plasterboard panels and metal profiles represent today and in this (foreign) place?

A similar question is raised by the porcelain trophies presented on the metal profiles in their new function, as hybrids of sculpture and display unit. In collaboration with the venerable Viennese porcelain manufactory Augarten, whose handmade products are recognized worldwide, Dejanoff has designed a total of nine different cups and trophies. They are partly based on his preoccupation with the football player Trifon Ivanov, known as the Bulgarian wolf, who, like himself, comes from Veliko Tarnovo, and about whom myriad eccentric rumours abound. In the context of this exhibition, they once again combine with Dejanoff’s investigations into diverse representational forms, which do not remain trapped in the objects, but inscribe themselves in the many interstitial spaces of history, architecture, the sites and in the viewers themselves.